Inside The Lab this week, we had a call discussing what makes a great product. One member was considering transitioning a live, cohort-based course into a self-paced course – but was concerned that the decision might negatively impact student success.

The consensus among the group was that, yes, student success would probably suffer.

I've heard many numbers shared for the typical completion rates of self-paced courses (some as low as 4%). Could it really be THAT bad?

I looked at my OWN student data in Teachable (my current LMS) and saw average course completion between 27 and 46%, depending on the course.

But this brings up some important questions:

- Who is to blame for the poor completion percentage?

- How high should we expect these completion percentages to be?

- What makes for a "good" course?

Who's to blame?

As a course creator, you may be quick to blame low completion rates on the student. After all, if the information is all there and they didn't take the time to internalize it, isn't that their fault?

Probably not.

Do you finish every book you pick up? Every video you start watching? Every movie?

Of course not. When we start something, we have good intentions and high hopes. We obviously think this is a worthwhile investment of time. But once you lose interest (or faith) in it delivering what you'd hoped for, you'll cut your losses and move on.

This isn't the only cause for low completion rates in digital products, but it's a big one. When someone buys your product, it's because you've made some promise to them. A problem they want to be solved, a desire to experience, or some new future better than their present.

We focus our sales efforts on the outcome on the other side of the product. We make big promises for a better life – all you need to do is buy this [thing]. We make it seem so attainable that the act of purchasing itself feels like we're buying the outcome.

Customers buy the promise of value.

But at the point of transaction, the customer has taken all the risk. The creator captures value (in cash), but the customer is still at the starting line, waiting to capture their value in return.

We obsess and optimize for everything up to the point of purchase...and then we throw our customers into the deep end.

For many products, the starting line reveals a path much longer (and more difficult) than the sales page led on. Customers thought they were buying an outcome, but what they got was possibility of an outcome on the other side of a whole lot of labor. Lightly-organized information packed into videos that are typically longer than necessary.

What ACTUALLY makes a good product

Information products aren't inherently bad or ineffective. But recording a bunch of videos doesn't mean you've made a great course.

We think the value of the product is the information – but customers buy outcomes.

Information may be necessary, but it's not enough. Customers don't want a transfer of knowledge – they want a real outcome.

Your job is to make it easy to extract the value you've promised from your products.

Some products are easy – we know that templates, widgets, and software should be plug-and-play.

Other products – like courses and memberships – are harder to do well.

The Lab is nearly three years old and several members of The Lab have renewed twice already. Clearly, they're extracting enough value from the product that they decide to purchase it again and again.

...but, at the same time, other members didn't renew after their first year.

What's going on?

It's the same product and the same customer avatar...but while some get massive value, others do not.

What's the difference?

Reducing customer effort

In a membership community, the value comes from the relationships built. Building relationships takes effort! You may need to:

- Spend time in the forum

- Show up on calls

- Identify who you want to talk to

- Reach out to that person

- Be a good listener

- Provide value to THAT person

- Stay in touch

These are all potential points of failure on the road to extracting value. Building a relationship with someone takes time, courage, and emotional labor. If someone doesn't make that effort – and therefore doesn't extract value from the membership – who's to blame?

Well, unless you're offering a done-for-you service, the customer will be required to make SOME effort.

Your job is to maximize their return on effort.

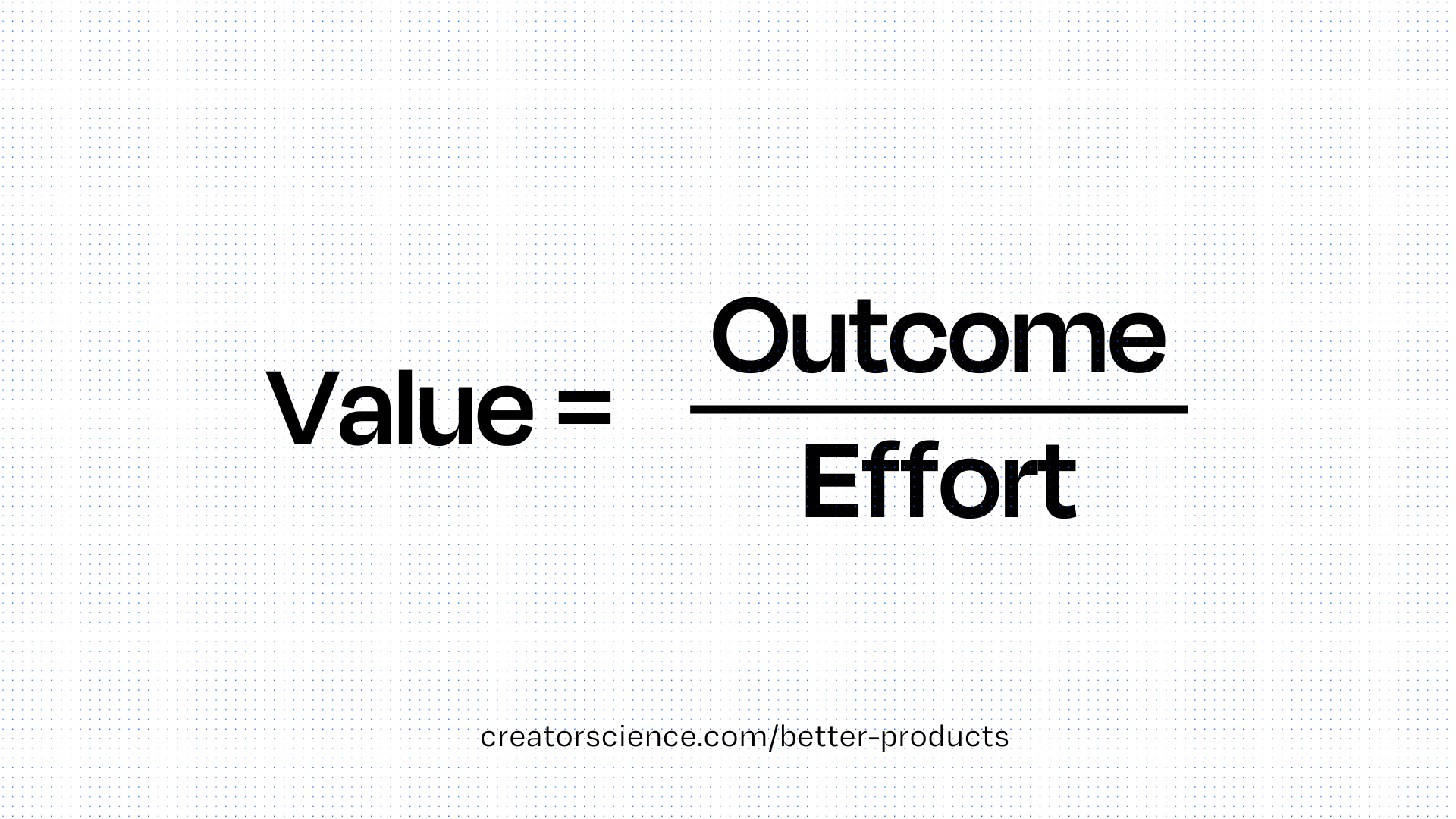

Think of Value as Outcome divided by Effort.

You can increase Value in two ways:

- Increasing the Outcome

- Decreasing the Effort

But the highest leverage comes from decreasing Effort. No matter how big the Outcome is, a large Effort required will reduce the overall Value.

Design your products to reduce customer effort as much as possible.

The more you reduce the Effort necessary for a customer to extract Value, the more likely they are to succeed. The more customers succeed, the more they share. The more they share, the more new customers buy. The more those new customers buy, the more customers who succeed...and on...and on...

This is why the Labmate was concerned about student success (and why you should be too). Student success is the flywheel that generates more students.

Look at the list above and consider what you could do to reduce the effort required. What if you created mechanisms to introduce those members proactively instead of just giving members access to the space?

Or, in the case of self-paced courses, what if instead of explaining the theory of how to do something, you created ready-made templates or resources? What if instead of relying on the student to remember to make time for your product, you sent them emails to remind them of their commitment and answer their questions?

When someone purchases your product, their next thought is, "Now, how do I get that outcome you promised?"

Post-purchase, you should answer that question as quickly as possible. This is why I have post-purchase email sequences for all of my products. It's why I built dozens of tutorials INTO CreatorHQ and an onboarding course in The Lab.

If students are failing to achieve the outcomes you promise, take ownership. Ask yourself how you can reduce the effort required for them to achieve those outcomes.

Products aren't successful because we're great at selling them...

Products are successful because they delivered the outcomes they promised.